KCU alumna and rural physician reflects on her path to family practice

When Elisa Vinyard, DO (COM ’00), graduated from high school and left her small hometown of Maysville, Missouri, she never envisioned she would wind up back there, especially not as a physician. At the time, Vinyard had her mind set on becoming a psychiatrist in a larger community with plenty of resources. Psychiatry seemed like a way to help people without the long hours she had seen her physician father work, and with the added benefit of avoiding blood.

But life had other plans for her. As an undergraduate student at Rockhurst University, Vinyard went on a medical mission trip to the Dominican Republic with her dad. During the mission, she had the opportunity to assist him with a surgical procedure. “Somehow, I avoided passing out, and that gave me the confidence that I could be okay around blood,” said Vinyard, with a laugh. She credits her faith for changing her mind about pursuing medicine.

“It’s like I was going straight toward psychiatry and then God turned me 90 degrees to focus on becoming a family practice doctor.” Her conviction that medicine was the right path for her has never wavered since entering medical school at KCU. “I believe medicine has to be a calling because it’s really hard work,” she said. Thankfully, it’s work she loves among people she loves.

Since completing her residency at the Medical Center of Independence in 2003, Vinyard has worked in family practice with her dad, also an osteopathic physician, at Maysville Family Health Clinic and in a neighboring community at Cameron Regional Medical Center.

“I literally grew up in the [clinic] building in Maysville,” she said. She spends half her clinical time there, half in Cameron and does hospital rounds in Cameron. When asked what compelled her to return to her hometown to practice medicine, she answered, “I knew I wanted to help people, and I wanted to be where there was a great need. To me, the need was obvious in my rural community.”

One of the challenges of working in rural healthcare is a lack of access to specialty care. Specialists from larger cities visit rural communities, but those visits are still unable to meet all the needs of the community. It can be difficult to get patients the care and treatment they need when they live far from hospitals, clinics and pharmacies. Some patients have to drive 20 miles or more on a gravel road to get the care they need. Still, Vinyard is convinced that the opportunities for physicians in a rural setting outweigh the obstacles.

“You get to do almost anything you are certified for, so you don’t have to do the same thing day in and day out. You have a lot more freedom than in a larger system where you have to specialize,” she offered. Another perk of being a physician in a small town is seeing patients across the lifespan. Vinyard cares for patients from newborns to centenarians, her oldest patient being 111.

“My patients are incredibly special to me because we’ve been in each other’s lives for so long,” she said. Living among her patients and being in close community with them allows her to provide an extra level of care and treat the whole person. Her background in psychology comes in handy when she attends to the emotional needs of her patients.

Vinyard wears many hats as a rural physician. She is the medical director of Cardio-Pulmonary Rehabilitation at Cameron Regional Medical Center. She also serves as medical director of The Village Residential Care Facility and Cameron Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, a skilled nursing facility.

She is the information technology provider liaison for the hospital system, educating her peers on the newest technology to help them provide leading-edge care to their patients. She sees technology as a powerful way to enable the work physicians do as long as it doesn’t hinder the human connection between provider and patient.

Vinyard wears still more hats at the state and national levels as an advocate for policies and procedures that benefit physicians and patients. As president of Missouri Association of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons (MAOPS), she works with association colleagues to uphold the integrity of required education hours for medical providers who practice as physicians.

MAOPS is also fighting interference laws that allow politicians to get between patients and their doctors, compromising quality of care. Both in her role as president of MAOPS and in her role as Missouri delegate to the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), she is able to act on her passion for patients receiving personalized, high-quality medical care.

With nearly 20 years of experience as a physician and almost 18 years of experience as a mom, Vinyard has learned a lot about work-life balance. Her advice for new and future physicians to help them achieve their own personal and professional goals is, “Be open and honest with yourself and with potential employers about what you want your life and your practice to look like.”

For example, if you don’t want to work 60 hours a week, communicate that. If you have a passion for a certain specialty or an area of practice you want to avoid, let that be known. “It is possible to have a family, a personal life and a career in medicine, but you have to prioritize. There will be phases in life where one wins out over the other and you have to play catch-up later,” she said.

She reluctantly counts herself among the many physicians who are driven, Type A personalities and believes they need to have people in their lives who help them set limits and boundaries to stay healthy and balanced. She has found that it helps to surround herself with the right support system.

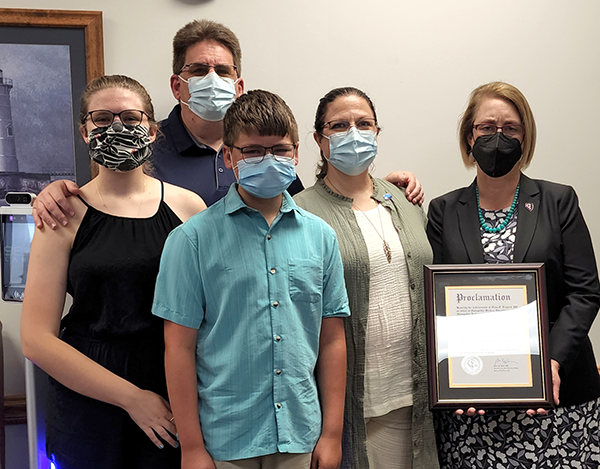

“You need people in your life to rein you in and keep you from doing too much and burning out,” she said. For Vinyard, those people are her husband, her kids and her closest friends. For this physician, wife, mom and friend, her loved ones take care of her so she can take care of her community.